Sinners (2025): The Illusion of Final Cut

Let me be upfront. I hadn’t watched any of Coogler's work. Not out of protest, just disinterest. Franchise reboots, spandex and pew-pew lasers forged from Video Copilot assets, that's background noise to me. On that note, I wasn’t planning to watch this one either. Frankly, nothing about it looked remotely interesting.

Then I stumbled on this opinion piece in The New York Times titled “The Movie Deal That Made Hollywood Lose Its Mind.”1 It's classic headline pornography dressed up as cultural critique. Ah well, that’s the state of legacy media. Clarity sacrificed for engagement.

The piece falls apart right after this nugget of modern rhetorical fog, "... and in fact his copyright arrangement is unusual, but not unprecedented.” You’re left scratching your head while journalism slowly bleeds out. Like a pensive man who consumes freeuse incest porn, convinced the plot will improve... and yet, I kept reading anyway.

Now, you may ask…

Unlike Gunasekaran, I’m no pro se hero. I’m simply questioning. My interest isn’t in the "deal" itself, but in the F word and the opacity surrounding it. The piece, like all its legacy media counterparts,2 stumbles through explanation, yet clings desperately to the words “final cut” as if repetition alone could summon clarity.

Simply put, final cut is a mantle, and Coogler has yet to claim it. That’s not a dismissal, it’s a fact. He might get there, but right now the filmography is thin and if Warner Bros. handed him the reins without guardrails, then something else was in play. And that, more than Coogler, more than the budget, more than ownership, more than the political signaling tied to hues other than #FFFFFF, was what I was curious about. அப்படி இதுல என்ன சிறப்பம்சம் இருக்குதுனு பாத்துருவோம்...

So there I was, firing up the media platform from that trillion-dollar orchard, boasting a logo that is emblematic of humanity’s expulsion from Eden. Dropped a hefty twenty. Clicked play. Skipped the trailer for The Studio because I have yet to experience even a flicker of comedy from anything involving Seth Rogen.

Logos. Fade in. And here we go...

Strike 1

The film opens with a Ken Burns style slideshow, steered by a voice-over. Immediately, a quiet nasal puff escaped my nose. Fine, I said. Lazy, but fine. I say lazy, because there’s nothing in that slideshow you couldn’t stage live with half the effort. Then, the very first slide is split in two, bridged by a dissolve (Figs. 1.1 to 1.3). Now, the corner of my eye starts to twitch. Just shy of a frown, but from the inside. That dissolve feels unmotivated. Unnecessary. And I find myself asking, not out loud, but inside my head... why?

Figs. 1.1 to 1.3

Figs. 1.1 to 1.3

The voiceover drones on top:

There are legends of people born with the gift of making music so true, it can pierce the veil between life and death, conjuring spirits from the past and the future.

That’s a cute and vague description, but why break the slide just for that one line? Why not let it stand on its own by adjusting the timing? You matched the timing for the later ones, though the push-ins on one slide and pull-outs on the others are jarring. But hey, for a director with “final cut” privileges, I guess it’s okay to forgive these basic visual communication messes. So I ask again, what makes this one so special?

My feeble, senile man shaking his fist at passing clouds guess would be: the “evil spirits” are placed farther away than the man with the guitar to reveal that quadrant of the frame before the line ends — or — the original narration was probably longer and, for some odd reason, got cut. That’s fine. These things happen.

So what did Mr. Coogler do? Well... the man with future ownership and the story he wanted to tell since he was in his mother’s womb, the one for the “culture,” and yes, the man with "final cut" privileges simply patched it with a dissolve. Got’emmmmmmmm!

This isn’t a technical compromise. This is a creative complacency by choice. I mean, you could have masked around the “evil spirits” and brought them closer, nested the slide as one, and then pushed or pulled, or dragged, or shoved — I don’t fucking care at this point. Or you could have just timed it properly, like I did here.

At that point, I paused the film, turned to my wife, and muttered, “He had the final fucking cut!”

Strike one my love.

Strike fucking one.

Moving on...

Strike 2

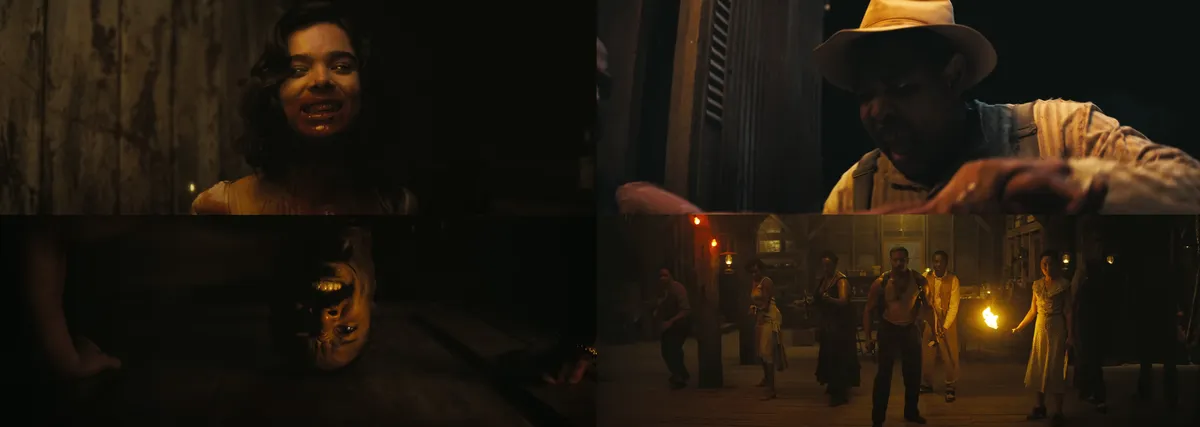

The opening sermon scene is designed to build tension by holding back just enough information to make you lean in. The bruises, the broken guitar, the silence. That was the hook. Cool. But just as it starts to reel in, it gets derailed by a burst of prematurely ejaculated insert shots (Figs. 1.4 to 1.7). They’re rapid, impossible to parse, and they come bundled with sound design straight from a free sample pack of “Extreme Trailer FX”. The kind you’d find in the starter kit of an influencer bro-turned-content-creator-turned-filmmaker-turned-entrepreneur who promises to teach you how to make six figures with this one trick. As a result, the tone clashes, the pacing collapses, and worst of all, the mystery is spoiled before it even has a chance to take shape.

Figs. 1.4 to 1.7

Figs. 1.4 to 1.7

To me, this isn’t creative. No sir, this is reactive. My feeble, senile man shaking his fist at passing clouds guess would be: this is a studio note, possibly routed through marketing who asked Coogler, “How do we tell the audience it’s a bargain bin version of From Dusk Till Dawn with a dash of Mississippi Burning with a sprinkle of The Great Debaters with a lot of The Hateful Eight without telling them it’s a bargain bin version of From Dusk Till Dawn with a dash of Mississippi Burning with a sprinkle of The Great Debaters with a lot of The Hateful Eight?”

To be fair, I have a hard time believing Coogler kowtowed to the note. You could argue against those insert shots without even trying, just by pointing to the floating heads poster or the trailer. It already reveals the buy-one-get-one lead, the vampires, and the obligatory “team spandex assemble” formation (Fig. 1.8). It’s not that they were concealing an A-lister for a pivotal third-act moment à la John Doe or Dr. Mann or even simply keeping the buy-one-get-one lead under wraps. Everything was in the open anyway.

Fig. 1.8

Fig. 1.8

But then I come back to the whole final cut thing. That means Coogler reviewed this version, sat with it, and said, “This is the one.” Not because the story needed it, but because someone had to calm the skepticism of a studio spreadsheet by wind-tunnel testing the market. It just makes the whole thing feel more... corporate.

This isn’t storytelling Mr. Coogler. It’s fucking high budget content. It’s the cinematic equivalent of a reel where the caption’s outline stroke is thicker than the text itself, screaming “Wait till the end bro!” Except I already know Mr. Coogler. Because you just fucking showed it to me Mr. Coogler! And somehow, you still want credit for the surprise Mr. Coogler?

I paused the movie... again. Turned to my wife, and muttered... again. “He had the final fuckity fucking cut!”

Strike two my love.

Strike fucking two.

Moving on...

Strike 3

The last strike wasn’t in the story’s structure; it was in the writing and the performances, each collapsing under its own cleverness. Around the fifteen-minute mark, one of the twins or cousins or inbreds — I don’t fucking care at this point, delivers a TED Talk on negotiation to what I’m supposed to believe is a little girl, sitting on a front stoop, picking a daisy in 1930's rural Mississippi (Figs. 1.9 to 2.2).

He walks over and asks, “Do you know the Smoke Stack twins?” She replies in a flat, Los Angeles film school accent, “Of course.” The scene’s authenticity is about as convincing as their caricatured Southern drawl.

But, wait a second… I wondered. She didn’t even ask for this. She was just sitting there, picking a fucking daisy. Then I wondered further… did தோழர் Vetrimaaran write this? Did தோழர் Coogler got inspired by மக்கள் படையின் தலைவர், தோழர் பெருமாள், the man who hands out TED talks on negotiation, communism, and labor laws, delivered about a hundred frames off sync, though no one invited the lecture?

Figs. 1.9 to 2.2

Figs. 1.9 to 2.2

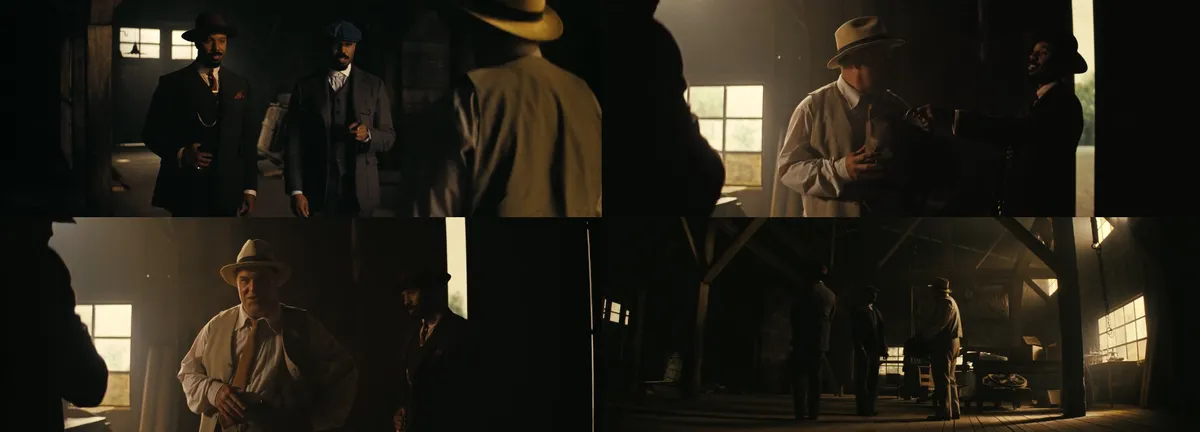

How am I supposed to believe, or even pretend, that this is all organic? This same character, just a few scenes earlier, buys out a sawmill by handing over a bag of cash (Figs. 2.3 to 2.6) without pushback or a counteroffer and now he’s standing there, giving a lecture on strategic financial thinking?

Figs. 2.3 to 2.6

Figs. 2.3 to 2.6

Ain’t no boys here. Just grown men. With grown men money. And grown men bullets.

Whatta writingg yaar!? Instead of what could have been a demonstration of tactical negotiation skills, something that might actually add depth, or, I don’t know, maybe have the characters introduce each other by name, I get empty bravado, baseless trade, and hollow threats. Fucking poetry in motion. I can just picture Coogler, in front of his screen, reading what feels like it was spat out by an AI prompt, nodding to himself — “Got’emmmmmmmm”

But I get it. Films like this need a moment of moral wisdom for… sigh… say it with me now, "Won’t somebody please think of the children!" For my readers across the ocean, that is a catchphrase from a beloved Simpsons character, Helen Lovejoy — the reverend’s wife who plays the town’s socially conscious concern troll all while being just as hypocritical as the rest of us. But hey, not yours truly. Never. Anyway, you’ve got to wedge in an intergenerational empowerment scene to justify the screenplay’s faux depth.

My issue isn’t with the message à la கருத்து கந்தசாமி or the crowd it’s preaching to. Because, the kids are fucked beyond repair. They’ll slip right between influencers peddling gambling addictions and Instagram models, jet-setting by day, used as potter potty by wealthy sheikhs by night, crossing puberty only to graduate into premium adolescent content, all while hawking discount codes for scam therapy apps, shitty earbuds, and some green ass juice. Oh, it’s coming, folks! When desire is commodified, weakness is monetized, and vice packaged as content, age dissolves into irrelevance. Morality is optional, and no one is safe from the algorithm. அல்கோரிதமிற்கு அரோகரா!

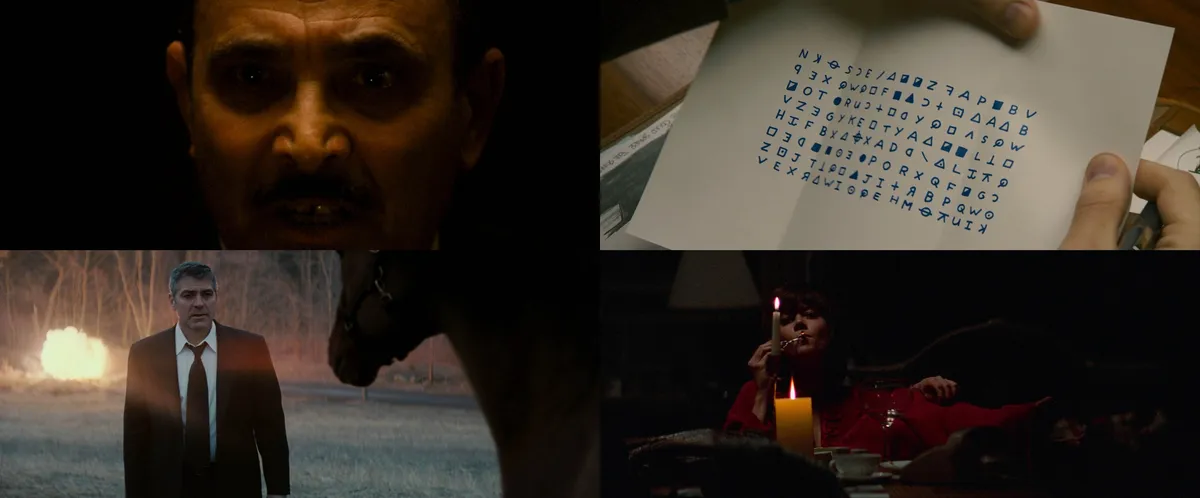

No — my issue is with the hypocrisy of the message. Because the same guy who gave the TED Talk on negotiation, the same guy who bought a sawmill without any counteroffer, moments later, shoots two men over something that could have been solved easily with words (Figs. 2.7 to 3.0). What the fuck happened to those elite negotiating skills, mister?

Figs. 2.7 to 3.0

Figs. 2.7 to 3.0

To me, this scene feels as if Coogler shoehorned it in as a clause to ensure the film got made. I can just imagine him at the negotiation table going: "One intergenerational ownership lesson for me, and a good ol' dose of Hollywood-style violence to perpetuate that same ownership lesson for thee." He then leans back. A dramatic pause follows. We cut to the suits, huddling, whispering. Then cut back to a wide of the table. As we push in on Coogler’s face, off-screen a studio exec calls out, “You got a deal.” Coogler presses his knuckles to his lips, a quiet exhale of triumph as his mind mutters — “Got’emmmmmmmm”

Again… I paused the movie.

Again… I turned to my wife.

You know the slogan by now.

Strike three and I checked out.

Fifteen.

I gave Sinners a proper share of my time. And let’s be clear, these aren’t nitpicks. These are basic elements. Fifteen minutes in, and I’ve got nothing. I don’t know who these two leads are, and frankly, I’m not compelled to find out. That’s not on me. That’s the film refusing to meet me halfway.

In those same fifteen minutes, we met the Corleone family and got a glimpse of their busssiiiness. The first Zodiac cipher was cracked. Michael Clayton's Mercedes S-Class went boom! Marla showed up at the testicular cancer meeting. Bree got her first phone call in Klute. Harry Caul listened… forget fifteen, if you miss just the first five of The Conversation, you are lost. Detective Park Doo-man and Seo Tae-yoon’s partnership got "kick" started. Maya’s claim about Bin Laden got her noticed by Dan. Chief Gillespie accused Virgil Tibbs of murder, unaware of who he really was. Meanwhile, Velu Bhai, the son of Rajalakshmi and Sreenivasan, embarked on his first smuggle run, setting him on the path to becoming the great Yakuza, Rangaraya Sakthivel Nayakar!

That's fifteen minutes mate! You miss a beat or come in late, and you’re not just lost in the sauce... you’re out! There is no handholding and no soft landings. Not because the directors lacked patience. They just didn’t see the point in wasting yours. Every frame had purpose. Every cut meant something. That’s filmmaking. Or at least, it used to be.

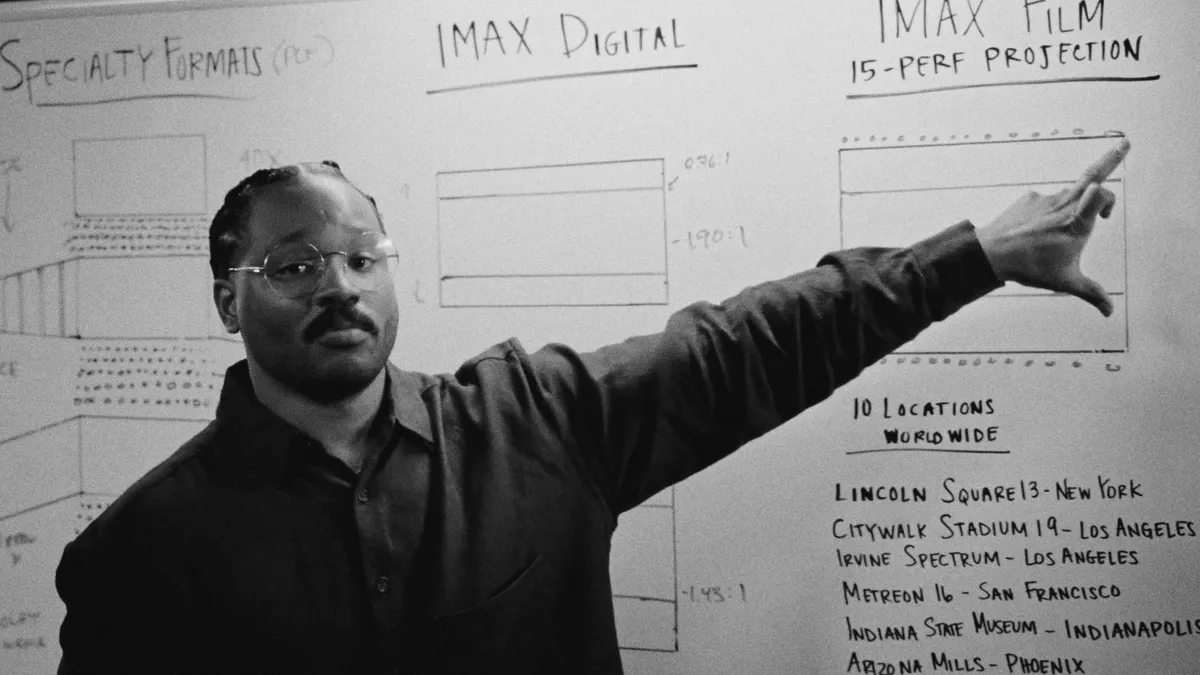

Technical excess

I have no doubt Coogler is fascinated by celluloid, yet the cinematography contributes nothing memorable. I’m aware of the whole parade of cross-pollinated promo videos Coogler did with Kodak, IMAX, and the ASC, just to name a few. All the same safe, PR-approved spiel, perfectly polished to sell the brand while the film barely gets a thought. Let’s be honest, who the fuck cares about format or perforation? The story stays the same. The characters stay the same. It’s all just technical noise with no intention of supporting the film.

What gets me is the disconnect. Here’s a movie parading its “shot on IMAX this,” “X-perf that,” anamorphic this, twinning technology that, but the final frame might as well have been composed for basic cable. If you're going to shoot in those formats, use them. But beyond that, I keep asking, was any of it even necessary? What about Sinners demanded a vertically dominant format, only to be presented like any other widescreen drama? All of the extraneous efforts for image acquisition feel like the cinematic equivalent of renting a helicopter with a gyrostabilized camera just to film an Aaron Sorkin walk and talk.

It's subjective bro!

I’ve been observing this deflective pattern for a while. It’s small, but it’s everywhere. You see it most in modern film criticism, and dare I say, in communication in general. It’s the habit of presenting indecisiveness as a point of view. Sure, art is subjective and interpretation leaves room for debate. I’m not arguing with that. But that also doesn’t make every creative decision immune to scrutiny.

Using subjectivity as a shield for sloppy storytelling isn’t just lazy. It’s evasive, and I’d go as far as to say it’s profoundly dangerous. It’s evasive in that it grants a convenient escape from accountability and kills the possibility of genuine dialogue. It’s dangerous because it discards the shared language of cinema, the intelligence of the audience, and the very logic that underpins narrative art.

This kind of thinking makes critique sound like static noise, blurring the line between a filmmaker’s intent and what actually ends up on screen. Sooner or later, the language of film has to mean something. Otherwise, it’s just a series of empty moves pretending to be cinema.

The pitch.

Everywhere you look in the press material, Coogler sells this film as deeply personal. Depending on which interview you read or listen to, he oscillates between two tales. One is the bluesy story about growing up middle-class in Oakland, the outsider, the music nerd, the lifelong storyteller waiting for his one shot, one opportunity, palms sweaty, mom’s spaghetti and all that. The other is the whole thing about demanding for ownership, which is apparently less about power and more about personal symbolism. Whatever that even means. And somewhere in the mix, there is Tupac. I kid you not. That’s the pitch. Fine.

If that’s the sell and you’re granted a $90 million budget, technical gluttony, final cut, and future ownership, shouldn’t the work rise above the noise? Maybe, I don’t know, a little more personal? Or at least skip the same reprocessed sludge clogging up the culture? A creative decision carries weight only if it holds up under pressure. Otherwise, it’s just noise pretending to be intention. When your choices start serving anything but the story, you’re not directing. You’re formatting.

Most people couldn’t tell a final cut from a rough cut any more than they could explain why they like Spielberg and they don’t need to. What matters is that they feel it — or feel its absence — in every frame. They may not know the difference between having their eye directed in a scene that’s a oner and one stitched together from coverage, but their instincts do. Audiences understand the grammar of cinema, even if they can’t name it. They know when an emotion is earned in a close-up, implied in a medium, or withheld in a wide.

Sinners, however, with its pacing, rhythm, dialogue, and editorial choices, fails to meet even the basic standards of film language, let alone justify a final cut. At best, it’s a pastiche of 1930s Mississippi, shot on film with contrast so heavy it collapses into its own darkness. I mean, if you call your film personal, shouldn’t it change the way you change? Otherwise, what’s so personal about it?

A wet flare

The more I reflect on this, one thing stands out. And that is, this “deal” isn’t really about Coogler. Or ownership. Or even the final cut. This “deal” is a flare. Not just any flare. It’s Dr. Stanley Goodspeed running at 60fps... kneeling at 120fps... F/A-18 Hornets shredding the skies at dusk... kids from the rural Americana gaping and pointing at them... Hans Zimmer blaring brass... the Star sand Stripes flapping in glory... fireworks blazing... full fucking Bayhem green smoke flare for the New Hollywood wave legacy directors.

It's for those who carried the flame forward from the Modernist wave, shaping the studio system we know today. Those same directors are now being poached by streaming services, handsomely compensated, and most importantly, freeing them from rigid rules and the endless grind of defending every choice.

As much as I dread enshittification, technofeudalism, surveillance capitalism, or whatever label you want to stick on Silicon Valley’s systematic erosion of media literacy and the sodomization of arts, Scorsese could never have funded The Irishman without their hand in the game.3 Yes, De Niro looked like a wax statue and moved like a claymation figure, but the film still breathed like only Scorsese could make it. Same goes for Mank, a project Fincher wished to undertake following The Game, but Polygram refused, citing its black-and-white format.4

Netflix, the very company that first named “sleep”5 as its greatest rival and later changed that to “screen time,”6 stepped in to breathe life into these projects, leaving me to reflect on the eternal conundrum — நீங்க நல்லவரா? கெட்டவரா? So, the message is loud, clear, and desperate. “Come back. We’re giving away final cuts now!”

Linguistic bait-and-switch

I’ve written about this before in my post titled From ‘For’ to ‘With’: The Slow Corruption of Language, and this is a continuation in the same vein. The studio system is stumbling, held together by denial and duct tape, and in some desperate bid for relevance, it's handed off to corporate doublespeak fuckery. Just like they turned “large” format screens into “premium,” and shot with IMAX to for, the latest is rewriting the meaning of “final cut” to mean "ownership." Motherfuckers, they are not the same! You say you care, but you don’t even know what you care about. And still, you stumble!

Fine. I’ll play your fucking game. Ownership after twenty-five years sounds meaningful, even noble, at first glance. But when you step back and really consider the value of the deal, it starts to feel more like a calculated piece of marketing than an actual creative victory. Because I can’t imagine anyone wanting to invest more time after the first watch, the film has zero rewatch value. I mean that in a kind of pseudo-objective sense.

Yeah, I know, after ranting about doublespeak, here I am pulling one myself. What I’m trying to convey is this: as time stretches and reshapes us, the films we tend to like and love stretches with it. You return not because you want to, but because they still have work to do on you. They hold details you missed back then, but that matter now. They hold your hand and pull you deeper into your own experience, offering something new each time, revealing something that connects, mirrors, and/or even transcends. Sinners isn’t that kind of film. It's empty and hollow. To be clear, the film isn’t hollow because it has nothing to say; it’s hollow because it doesn’t say it well.

Victory Without Value

This whole "deal" brings to mind the punch line of Vivek’s comedy in the film Lovely (2001).

பாரின் ஷூவ திருடிட்டு ஒரு கக்கூஸ் செப்பல்ல போட்டுவுட்டு போறாங்களே! டேய், ஒரு ஷூவை வச்சி நீ என்னடா பண்ணுவ? ஒரு செப்பல்ல வச்சி நான் என்னடா பண்ணுவேன்?

A fitting metaphor for the redundancy of this trade. Neither party really wins here. The studio gets to say they’re empowering filmmakers. Coogler gets a trophy that never matters. The film sits trapped on a server farm and the audience inherits another lifeless slop they’ll ignore forever.

I don’t know if I’ll be around in twenty-five years, but if I were the one on the receiving end of Coogler’s legacy, I’d have questions about its value. If this is what my father left behind, with every resource at his disposal and complete freedom, and the studio just shrugged and signed off, then what exactly have I inherited? Legacy isn’t just tangible possessions or corporate doublespeak titles. It’s what you choose to preserve. The choices that define both your being and your labor, the principles that outlast your lifetime.

Final Cut: The Discipline of Defiance

If you track the insights of the greats, the roads of final cut all lead to the same destination. It’s not about artistic indulgence. It’s all about control and protection. Control over tone, texture, theme, and the story’s overall architecture. Protection of the heartbeat of the film, making sure the story breathes exactly the way the director intended it to.

David Fincher defines it: “Final cut just means that, at a certain point, you have the ability to end the discussion. You have the ability to say, ‘I understand. I see what you’re saying. I don’t think it’s a better version of this. This is what I believe in. This is what I want to put my name on.’”7

Sidney Lumet puts it as: "Final cut means that whatever I hand in as the final picture cannot be touched in any audio or visual component. This is the last thing any studio wants to give up, so it’s very difficult to achieve. I’d had final cut for many years, since Murder on the Orient Express. In those years, I don’t think more than ten directors had it. Before we had begun rehearsals on Daniel, Edgar asked me to share final cut with him. I explained that final cut was one of the most difficult things for a director to achieve, and was therefore precious."8

We’ve all heard the stories of directors who mortgaged their homes, torched their relationships, and gambled everything for the story they believed in. The Coppola story says it all. He lost his mind and most of his sanity trying to finish Apocalypse Now.9 Fincher fought to keep a single line in Fight Club.10 That was the battle. Or at least, one of them. Scorsese had to rely on producer Michael Phillips and former Governor Pat Brown just to get Taxi Driver’s X-rated version down to an R so it could actually be exhibited.11 Cameron fired his original cinematographer, clashed with the London crew, and fought the studio to keep Weaver in Aliens after they suggested cutting her over salary.12 And one of my favorites, my boy Bay writing a personal check to Columbia Pictures for ten grand (maybe twenty) just to shoot the final hangar explosion in Bad Boys.13

These struggles weren’t about hubris or inflexibility. They were simply fights to get the thing made the way it was meant to be and to maintain the creative decisions intact. That is what final cut used to signify. Next to the battles that once defined final cut, one can objectively claim that there are no bruises on Sinners. There is no tension in the making. No hint of pushback anywhere, especially not from the studio. If anything, it feels comfortably made within the studio system. Designed and approved by it. And this is the part that cannot be ignored. Without that struggle, what does final cut truly signify… if not the very scars of conviction?

Thanks for reading,

V.

The Movie Deal That Made Hollywood Lose Its Mind by Tiana Clark, The New York Times, May 3, 2025.↩

Not just this article, but a quick search for “Sinners + final cut” will turn up a slew of puff pieces, all treating the ordeal like it’s somewhere between the invention of the printing press and the second coming of Christ.↩

Martin Scorsese states he worked with Netflix out of “desperation” in the making of The Irishman on Directors Roundtable: Todd Phillips, Martin Scorsese, Greta Gerwig, Noah Baumbach, The Hollywood Reporter, January 6, 2020.↩

Magnificent Obsession: David Fincher on His Three‑Decade Quest to Bring ‘Mank’ to Life, Brent Lang, Variety, November 18, 2020.↩

Netflix CEO Reed Hastings: Sleep Is Our Competition, Rina Raphael, Fast Company, November 6, 2017.↩

The Netflix Chief’s Plan to Get You to Binge Even More, Lulu Garcia‑Navarro, The New York Times, May 25, 2024.↩

David Fincher Discusses Having Final Cut, Themes & More by Alex Billington, December 23, 2011, Firstshowing.net↩

Sidney Lumet, Making Movies (Vintage, 1995), p. 45.↩

Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse (1991) — Documentary on the making of Apocalypse Now, detailing Francis Ford Coppola’s epic struggles during production; Apocalypse Now: 4K Blu-ray 40th Anniversary Edition (2019) — Includes extended commentary and discussion with Steven Soderbergh at the Tribeca Film Festival. Released on Blu-ray in 2019.↩

Sharon Waxman, Rebels on the Backlot: Six Maverick Directors and How They Conquered the Hollywood Studio System (HarperCollins, 2005), p. 268; Chuck Palahniuk, interview on The Joe Rogan Experience, episode 1158, Fight Club’s Most Infamous Line, YouTube, August 22, 2018.↩

A magnificent article by Tim Pelan, Approaching Menace: The American Pathology of Martin Scorsese’s ‘Taxi Driver’, Cinephilia & Beyond, 2018.↩

Yet another insightful piece by Tim Pelan, The Risk Always Lives: Words to Live by On the Set of James Cameron’s ‘Aliens’, Cinephilia & Beyond, 2019.↩

So… I stay away from “trust me, bro” citations, but in this case, you have to trust me. The actual footage appears in the DVD special features of Bad Boys, showing Bay signing the check addressed to Columbia Pictures before calling action on the explosion as a nudge to the studio. I watched it circa 1998, definitely before 9/11. Furthermore, he also mentions it in the commentary tracks on both the DVD and Blu-ray editions. Here is a review providing evidence of what I described (though I might be off on the exact amount): Bad Boys DVD Review by Rich Goodman, MyReviewer.com, June 8, 2010↩