வாழை (2024): Shortcut to Sympathy

There is a kernel of truth somewhere at the core of Vaazhai—a memory so personal, so raw, it could have resonated universally. But as that kernel unfurls into the broader narrative, it begins to feel more like a carefully constructed artifice. Not in the sense of being fictional, but in the way it’s presented. The story doesn’t unfold organically, instead, it feels as if it’s been shaped not to follow, but to fit a certain emotional trajectory. Mari Selvaraj might as well have added a third opening card that says, 'Wait for it... ' and, at the interval block, telegraphed another card that says, 'What happens in the end will shock you... so wait for it!'

The film seeks to invite me into a meditative space, cajoling me to synchronize with the rhythm of its narrative. But when essential information is mishandled and conveyed with such disjointedness—quite literally disrupting the synchronization—it becomes not merely difficult to follow the narrative, but a chore. It seems to actively encourage me to disengage, as if it had grown tired of its own attempt to communicate. The very act of watching Vaazhai becomes a burden, let alone feeling it.

Trouble with form

Cinema is its own language. It doesn’t just speak. It manipulates. It breathes through frames, through cuts, through angles—each one meticulously designed to convey meaning. Each frame a word. Each shot a sentence. Each sequence a paragraph. Each scene a chapter. Beneath this, hidden in the bedrock, lie the phonemes and morphemes—the silent architects of meaning. The pause before a line is spoken. The cut just before the action unfolds. These are the building blocks. Without them, the language collapses. The very foundation remains unformed, and the story never comes to life. A film without its foundation isn’t just weak. It’s nothing at all.

One of the most troubling aspects of Vaazhai is its lack of cohesive form. There’s ambition, undeniably—a desire to evoke something deep, something real. But without a clear structure—or cinematic signposts, if you prefer—the multifaceted nature of trauma, its aftermath, and the understanding of its suffering starts to blur. Without that form, the narrative becomes formless, and the concepts Mari Selvaraj tries to explore fail to take root. As an audience, I’m left scrambling, chasing threads that never quite connect.

Overcomplicating Simplicity

At its core, Vaazhai is a pretty straightforward story. A young boy, on the verge of adolescence, brimmed with hormones, reluctant to spend his weekends working. One day, he manages to dodge work, and somehow, Mari Selvaraj tosses in a real-life tragedy at the end, clumsily attempting to force a connection between that escape and the events that follow. But that connection feels outré. It all seems stitched together, as if he is desperately trying to force depth where none exists. That’s it. That’s the premise at its surface. Yet, it’s braided with an overabundance of pictorial complexity.

The flaw—or perhaps the gimmick, depending on your tolerance for indulgence in modern Tamil cinema, lies in this newfound obsession with overzealous complexity. When a story could unfold with grace, effortlessly, and without pretense, what purpose does it serve to complicate things? Why cloud a straightforward narrative with layers that don’t enrich, but instead distract, when clarity and simplicity would more than suffice?

Take the very first sequence, for instance, which lasts a full four minutes. For this simple story to take off, I’m flooded with three timelines. A fleeting false climax that serves no purpose, a montage here and there that serves no purpose, and, of course, those black-and-white sequences. Abstract. Pretentious. Why? What do they add? What’s the point? What exactly is Mari Selvaraj trying to communicate here? It’s a mess of form-over-function, a jumble of artifice trying to disguise itself as something profound when, in fact, it’s just convoluted. It’s as if he is actively trying to disguise something that was never as profound as he thought it was. And I can’t help but wonder—did he lose the story along the way, or was it never really there to begin with?

Aside from the black-and-white shots and slow motion, there’s nothing in this sequence to distinguish one timeline from the next. No visual or auditory cue to guide me through it. No anchor to steady me in this oscillation of time and space. I might understand the approach if there were something to make me care—anything. But there’s nothing. I’m adrift in each of these timelines, and it only deepens the confusion. We are off to a good start!

I gave you four minutes, Mr. Selvaraj. Four minutes of my attention, and what did I get in return? Nothing. No direction to follow, no thread to latch onto. Just frustration. Storytelling demands clarity. It’s about communication, above all else. Once that foundation is set, depth will emerge naturally. You can shape that depth with the tools at hand—timing, visuals, sounds, music, pacing. But when clarity is sacrificed from the outset, you gamble with everything. In trying to replace that void with something “more meaningful,” you fall into the trap of gimmicks. And that’s where it all falls apart. The illusion of depth can never substitute the essence of good storytelling.

Stumbling Through Subtexts

Mari Selvaraj loves his stylistic flourishes, visual metaphors, and narrative cues—each one seemingly designed to lead me toward the unsaid. At least, that’s what he thinks. But, honestly, these are nothing more than empty gestures, devoid of any real substance. Without a clear foundation of communication, all these flourishes and unspoken elements feel like mere decoration, aimlessly suspended in the frame. And I cannot help but wonder: What could have been if they were anchored in something deeper that I could actually hold onto?

Rather than offering clarity, Mari Selvaraj throws me into a labyrinth of ambiguity, one that doesn’t lead to understanding but spirals into more frustration. The elements for a somewhat cohesive narrative are present, but scattered haphazardly. No effort is made to connect these pieces, leaving me with nothing but fragments to cling to. It feels as though the very possibility of coherence was never even considered.

Now, I understand that some level of interpretation is always expected from the viewer, and I’m more than willing to engage with that. But when the intent feels intentionally obscured, when it’s clear I’m expected to “figure it out,” the experience shifts from being an engaging journey to a frustrating puzzle. Rather than being immersed in the story, I’m left expending all my energy trying to decipher what I’m meant to feel. And that’s when the connection to the narrative begins to break down, rendering the entire film fragmented, distant, and, ultimately, inaccessible. As previously stated, it becomes more of a chore than an experience.

Great cinema doesn’t demand interpretation—it invites it. It doesn’t bank on empty subtext; it ensures that the emotional core is felt, even if I, the viewer, can’t always articulate it.

Stumbling Through Subtext — Examples abound

1. Consider Sivanaindhan racing toward the elder’s funeral, eager to join his friends. One of the nucleus beats of the story. The passing of the elder is communicated in a quiet exchange through his sister’s words. That's enough to establish the event. In this moment, which should pulse with serendipitous freedom, the visuals undermines that possibility. Sivanaindhan's steps should not merely be an escape, but a blissful sprint into the unknown. Let every footfall resonate with promise, with the intoxicating elation of someone still on the edge of the world, someone with a future to chase.

If we look at the shot economy, Mari Selvaraj employs 15 shots within a span of just 43 seconds—each one disjointed, disconnected from the next. That’s 2.8 seconds per shot. Fifteen setups. Fifteen cuts. Fifteen opportunities to chart the trajectory of a character, to take us from point A to point B. And what do we learn? Does it teach us anything about the geography, the world that the character inhabits? Are we introduced to any members of his community? Any interactions that shed light on his emotional or social context? Nothing.

But what if, in those 15 shots, Mari Selvaraj had chosen to immerse us inside the world of Sivanaindhan? What if we had seen the people he encounters, the animals he interacts with, perhaps a local shop owner who waves at him or passing a cinema where he watches his Rajini films? There could be validity in that approach, a kind of world-building that deepens the character’s journey.

Mari Selvaraj’s decision to have him run toward death feels misaligned with the moment’s potential. Instead of this trajectory, the scene would benefit from a shift—rather than death, catapault him toward life! Show me the wild rush of youth, the unspoken promise of what’s ahead!

2. Once he enters the funeral house and joins his boys, to give credit where it’s due, the subtext lingers in the frame, though faint. Mari Selvaraj has the boys literally dancing in front of the corpse. Yet, the moment is framed from an objective vantage point, draining the scene of the emotional depth it could carry, leaving the subtext to float untethered. Yes, an elderly man has passed, and while his death may appear inconsequential, as nature follows its inevitable rhythm, this doesn’t absolve the film from overlooking the emotions of those who have lost him. It demands to be felt with the same weight, at least on par with the boys’ unscheduled freedomn that liberates them from the grind of labor on that very day.

The weight of the unsaid in the funeral scene rests in Sivanaindhan’s indifference to the loss. He is unmoved by the death of the elderly man, or by death itself, because, in that fleeting moment, it serves his own needs. His celebration is a sharp contrast to the somberness of the occasion. Therefore, to truly anchor the scene, the death—and by extension, the funeral—should have been rendered far more somber, far more haunting. Only then, with that gravity established, can Sivanaindhan's detached perspective take root, deepening the emotional dissonance.

The subtext, then, can be read as a dichotomy between life and death. To add another layer, it could underscore the unpredictable nature of existence. The same suddenness that takes a life is also the force that gives these boys a momentary reprieve. Once again, to fully grasp Sivanaindhan's joy, one must first feel the loss—the tension between the two emotional poles is what imbues the subtext with its necessary depth.

A quasi-parallel scene that illustrates this subtext can be found in Uzhavan (1993). In one of the comedic vignette, Chinni Jayanth sends Senthil to take a post-mortem portrait at a funeral. Completely oblivious to the gravity of the situation, and by extension, the significance of death, Senthil asks the corpse to smile. The absurdity that follows, though comedic, is steeped in subtext—revealing the ignorance toward the enormity of loss. This moment mirrors the emotional detachment in Vaazhai, where the boys dance in front of "death" without any understanding of its weight. The contrast in both scenes lies in how life persists in the face of death. One distorts it into farce, while the other underscores the boys’ elation, freed from labor for the day.

Uzhavan, directed by Kathir (Sai Shanthi Films, 1993).

Uzhavan, directed by Kathir (Sai Shanthi Films, 1993).

As an experimental exercise, I’ve taken the liberty of rearranging the scene to pose and explore: What is Sivanaindhan missing by being forced into labor? Or, conversely—and more profoundly—what is his existence robbing him of? By using the form of editing—intercutting between the weight of the elder's death and the pulsing rhythm of youthful life—let’s see if the scene can be improved to better anchor the subtext and allow the audience to reflect and feel at their own will.

Editor's note: For the sake of this experiment, let’s pretend that the mother, the sister, and all the other familial characters are complete strangers at this moment in the story’s timeline and within this cut. First, we’ll see the director's cut, followed by my own improvised cut.

Which version, in its simplicity, makes you feel the weight of what the boy's elation?

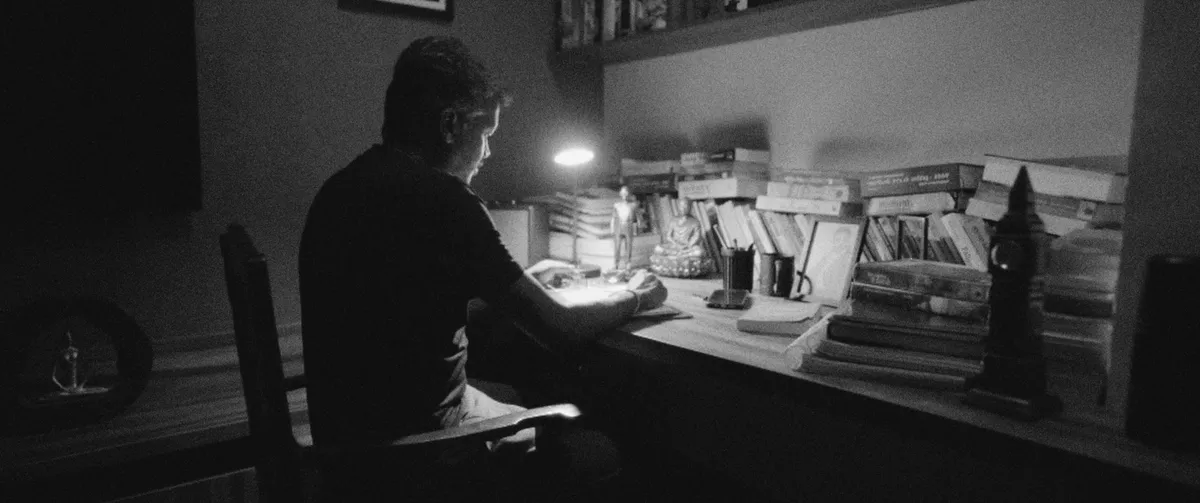

3. Don’t just tell me that he is a good student—show me. What does he read? What drives his curiosity? Show him poring over textbooks, scribbling notes in the margins, or eagerly seeking out knowledge beyond the confines of school. Show me the small, deliberate acts of intellectual effort—the way his eyes light up when he finds something new, the way he spends his free time absorbing facts, dissecting ideas. Let me see him hungry for more than just grades, so I can feel once again the education being stripped from him, every time he’s forced to haul plantains.

A quick shot economy calculation: we only get one scene clocking in at 1:22, aside from the school scenes. Even here, we don’t learn much—he’s just studying. I can only assume that Mari Selvaraj intended the oil lantern in the dark to subtly convey his eagerness, but it ultimately comes off as lazy.

The image of the “good student” is a lazy façade without any substance. It lacks the roots that would ground me as a viewer. Without the subtext of what drives his curiosity, what truly motivates him, it’s hard for me to emotionally connect to his education. I need to see and feel the why behind his actions. Only then will I be invested. If you don’t show it, I simply won’t care.

The image of the “good student” is a lazy façade without any substance. It lacks the roots that would ground me as a viewer. Without the subtext of what drives his curiosity, what truly motivates him, it’s hard for me to emotionally connect to his education. I need to see and feel the why behind his actions. Only then will I be invested. If you don’t show it, I simply won’t care.

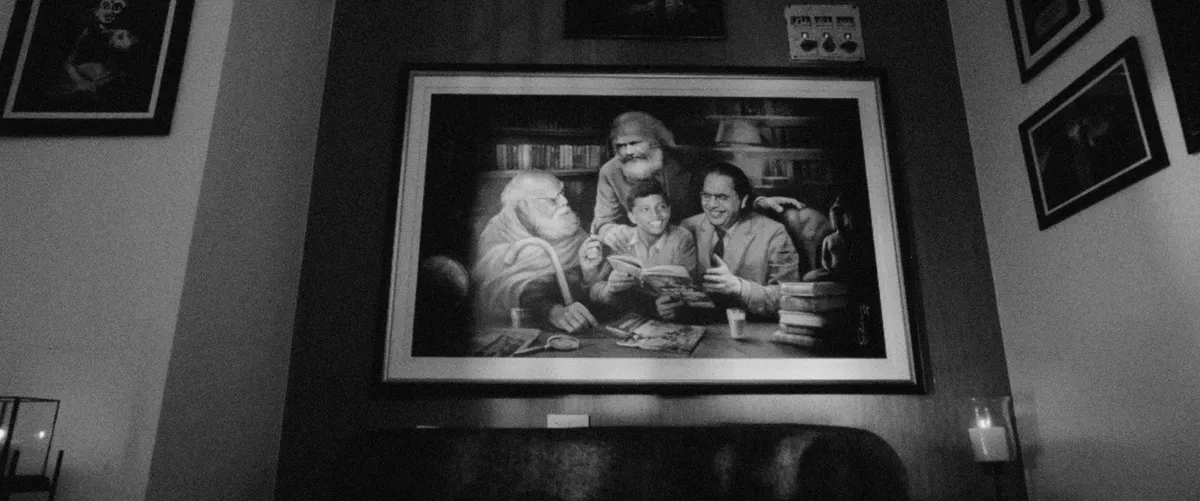

4. Apparently, the Rajni–Kamal reference is supposed to mean something. What, exactly, I’m not sure, and frankly, I’m not interested. But if the point is for me to understand the significance, don’t just tell me he’s a fan—show me. Show me him walking around with a popped collar, that signature Rajinikanth swagger. Let me see, in the intensity of his wide eyes, the depth of his focus, as he’s glued to the screen, memorizing every move, every line, as if each gesture is being branded into his soul. Then, flip the camera to his friend Sekar, dozing off, indifferent to it all. Now, reverse it for a Kamal Haasan film. Let me feel that same focus from his friend, eyes wide, while our boy, irritated (à la the Narrator, arms crossed, staring at Marla, the imposter hijacking testicular cancer), fades into a disinterested haze.

Pandian, directed by S. P. Muthuraman (Visaalam Productions, 1992).

Pandian, directed by S. P. Muthuraman (Visaalam Productions, 1992).

Use a period reference to draw the ‘right’ symbol à la Pandian! Have him sketch it on his shirt or in his school notebook—something that gets him in trouble with the teacher or a scolding from his mother. It’s a small, rebellious act, but one that speaks volumes about how deeply he’s influenced by the films he consumes. It’s not merely a symbol—it’s a fragment of his identity, a connection to the world through the characters who mold the fabric of his corner of the world.

Let the boys argue passionately over who the better actor is—not some generic, distant conversation, but with energy, with real investment. Maybe one argues that Rajni can't dance for shit, while the other says Kamal can’t toss a cigarette—whatever it is, let it be intense, but true to their age.

Most importantly, show me how they bond over something so seemingly trivial, yet so telling of who they are. It’s not about the idle mimicry—it’s about the connection, the energy these moments create between them. Don’t just slap a pendant or a picture on the wall, or use the Nayagan theme poorly and call it a day. Again, make me feel it.

5. The entire teacher sequence—including the song—spends a staggering 38:53 seconds on screen. That’s the longest shot economy in the film, and yet, what you feel is hesitation. Not from Sivanaindhan, but from Mari Selvaraj. Let’s not stand on ceremony here. If you’re going to go perverse, go all the way. Adolescence is messy. It’s reckless. And in that mess, there’s a brutal honesty. If you’re going to explore it, commit. This isn’t the time to fear backlash—that comes later.

We’ve all been there and done it. I used to not flip, but tilt those குமுதம், ஜெமினி சினிமா, and குங்குமம் to catch a glimpse of Ramba... wondering if she’s wearing any janga. அள்ளி அள்ளி அனார்கலி and ஈச்சங்காட்டுல முயல் ஒன்னு were part of my proudest faps. அழகிய லைலா got no shot, not with Gounder and Khadal Irvarasan Simpanndi stumbling around like a couple of drunk clowns. Yes. I too was a lecherous victim to her thighs. Yes. We're men. Men is what we are. Let’s reset after this brief detour into my take on the olfactophilia.

I'm not opposed to the act of sniffing the handkerchief, but I'm uncertain about the emotional intent behind it. The added wordplay with "பூங்கொடி" and the needle-drop of the same song feels forced, layering too much meaning without grounding it in Sivanaindhan's emotional arc.

As a thought experiment, imagine a dream sequence that doesn’t just hint at the crush, but shows its true impact—something surreal, visually striking. In this dream, it’s the annual day. He stands on stage, not simply performing but becoming the scene itself, singing பூங்கொடிதான் பூத்ததம்மா. But the stage itself is dressed in a way that recalls பொட்டு வைத்த ஒரு வட்ட நிலா, with its whimsical, dreamlike atmosphere. Behind him, a carousel of images of the teacher is rear-projected, as his teenage mind might imagine her—an idealized, distant and unattainable figure.

Idhayam, directed by Kathir (

Sathya Jyothi Films, 1991).

Idhayam, directed by Kathir (

Sathya Jyothi Films, 1991).

The emotional weight of the scene is carried by the lyrics, filling the space with youthful melancholy, "சிலருக்குச் சில நேரம், துணிச்சல்கள் பிறக்காது, துனிச்சல்கள் பிறக்காமல், கதவுகள் திறக்காது காட்டாத காதலெல்லாம், மீட்டாத வீணையைப் போல்". Then, in an instant, a slide of Sekar is projected, smudging the dream and snapping Sivanaindhan back to the harshness of real life.

Another interesting thought experiment. Borrow from Thalapathi, but don’t just copy—adapt it. Connect Sivanaindhan to his crush through a scene that feels organic. Imagine him at the village fair, surrounded by the vibrant chaos of the event. The laughter of children, the distant sound of music, perhaps "அடி ராக்கம்மா கைய தட்டு" blares through the megaphones. Amid the vibrant stalls, his teacher is there, engaging with villagers, perhaps even selling the pieces she sews, claiming to be a seamstress.

Our boy stands just a few feet away, his gaze fixed on her with longing. Show how his eyes track her movements in the crowd, how he's magnetically drawn to her without making it obvious. She doesn’t notice him, but the connection is palpable. This is where you can use with the form of sound. By toning down the diegetic sound and dissolving everything except for what he hears "அட உன்னப் போல, இங்கு நானும் தான்டி, அடி ஒன்னு சேர, இது நேரம் தான்டி." This isolated moment would amplify the intensity of the infatuation and allowing the viewer to feel with him. In the final strains of "ஜாங்குஜக்கு ஜா", Sekar could once again interrupt.

This "dream" mechanic itself could function as a recurring motif, playing with the audience’s expectations. What new strategy will Mari Selvaraj employ to disrupt Sivanaindhan’s dream next? Furthermore, this mechanic becomes an unfiltered window into the psyche of the character, amplifying his desires, fears, and contradictions without the need for elaborate exposition. And if the moral arbiters of society, those sanctimonious guardians of the CBFC, start scolding you for daring to push boundaries, all you have to do is pull the perfect escape hatch of "It’s a fucking dream mate!"

A quick side note—The most recent notable example that comes to mind is Sivaji: The Boss. In the first night sequence, just to set up a lead into a song, director Shankar employs six different setups across both Tamil and Telugu versions. Say what you will about him and his recent projects, but when the man commits, he fucking commits. For that level of dedication, he will always have my full respect.

Sivaji: The Boss, directed by S. Shankar (AVM Productions, 2007).

Sivaji: The Boss, directed by S. Shankar (AVM Productions, 2007).

I won’t claim to be an expert on the history of Tamil cinema, but from what I recall growing up, many comedic vignettes often relied on the "dream" mechanic. There was a distinct time when, despite the clear divide between hero and comedian, both characters were given a playground to explore their most absurd and uninhibited desires. The beauty of this approach was that comedy wasn’t just relegated to the margins. In fact, it often felt just as important—in some cases, even more so—than the main narrative. Each comedic scene was treated with equal weight and consideration, in terms of both plot and subtext, even when it veered into parody. There was a certain freedom in that structure, a reminder that sometimes the absurd can be just as meaningful as the serious.

A comedic vignette featuring Goundamani from the film Manikuyil (1993), where he daydreams about being infatuated with the butcher's daughter, imagining himself in a romantic scenario set to the song Darling Darling from the film Priya (1978).

A comedic vignette featuring Goundamani from the film Manikuyil (1993), where he daydreams about being infatuated with the butcher's daughter, imagining himself in a romantic scenario set to the song Darling Darling from the film Priya (1978).

A classic Vadivelu comedy from the film Manadhai Thirudivittai (2001) where he fabricates an elite version of his family to impress a girl, but in reality, they are nothing more than a local street dance troupe. Vadivelu hilariously embodies each member of the family, all in one frame.

A classic Vadivelu comedy from the film Manadhai Thirudivittai (2001) where he fabricates an elite version of his family to impress a girl, but in reality, they are nothing more than a local street dance troupe. Vadivelu hilariously embodies each member of the family, all in one frame.

Another comedic vignette featuring Goundamani from Puthu Paatu (1990), where he once again daydreams, imagining that he has scored a big sum of money, set to the song Raaja Raajathi from the film Agni Natchathiram (1988).

Another comedic vignette featuring Goundamani from Puthu Paatu (1990), where he once again daydreams, imagining that he has scored a big sum of money, set to the song Raaja Raajathi from the film Agni Natchathiram (1988).

What I’m alluding to is that humor, when done right, requires subtext. It’s more than just a break from the tension; it can enrich the character and add complexity to their emotional landscape. If done properly, this humor can make us care about the character more deeply, so that when they’re taken away or lost, the impact of that loss is felt much more profoundly.

Now, consider the way Sekar interrupts Sivanaindhan’s moments. Each disruption might seem like an innocent and annoying gag, but over time, it subtly builds an emotional connection. When Sekar is no longer there, the absence won’t just be a plot point—it’ll feel like a genuine, emotional cut for both Sivanaindhan and the audience. The loss will resonate, because the humor wasn’t just fluff; it was a crucial part of the emotional journey.

6. If hunger is supposed to carry weight in the climax, then Mari Selvaraj has a responsibility to make me feel it—and not just through dialogue or plot points, but with subtlety, texture, and emotional depth. The problem is that Sivanaindhan’s hunger—his yearning for sustenance—is non-existent up until the moment it’s force-fed into the narrative. I’m left wondering—don’t they serve midday meals at his school? What if we had a shot of the boys eating, or even Sivanaindhan stealing food from a friend’s lunchbox, like a nod to Mari Selvaraj’s own childhood? Something that could have gently seeded this hunger earlier in the film, making it feel organic and not like an afterthought. Then, out of nowhere, we get this masterclass of dialogue writing.

இன்னும் காலைல இருந்து சாப்பிடவே இல்ல அதுக்குள்ள போக சொல்ற?

அதனாலதான் மூணு சட்டி கொடுத்து இருக்கேன் காலைல ஒன்னு, மதியானதுக்கு ஒன்னு சாப்பிட்டாச்சு போறேன் மா.

சாப்பாடு கூட கொடுக்காம அனுப்புறேலே நீ...

போனவுடனே ஒரு சட்டியை கொடுத்து சாப்பிட வை

Then, we have the dance recital. I’m willing to suspend disbelief for a moment and accept that the energy consumption for dancing is far less than hauling plantains around—especially when Sivanaindhan is presumably so full of infatuation for his teacher that his physical limits are almost secondary. Fine, I'll buy into it. But when the performance ends, the narrative shifts.

This marks the point where I’m asked to invest in Sivanaindhan’s emotional trajectory, yet I’m given so little to work with—if anything at all. It’s maddening because the entire setup—the tension, the yearning, the obsession—feels completely hollow when it’s wrapped up so abruptly with no real follow-through. The teacher, in a token gesture, reminds me one more time that he’s hungry, and this exchange unfolds with yet another masterclass in dialogue delivery.

டேய், பசிக்குதுண்ணா வீட்டுக்கு வந்து சாப்பிட்டு போறியா?

“போற வழியிலே வயல்லே வாழைப்பழம் இடைக்கும் அத சாப்புடுகிறேன்”

She exits the frame, and just like that, she is gone. And thus I'm left with the mechanical closing of her arc. And then, without missing a beat, my boy is hungry again. At this point, Mari Selvaraj might as well turn on the house lights, walk center stage, wink at the audience, and say, "See what I did there? Now, that’s how you break convention! சினிமா எனக்கு எப்போதும் கீழேதான்!" Drops mic and pirouettes offstage for "அட விஷயங்கள் பல அறிஞ்சவன் நான், வெவரங்கள் பல புரிஞ்சவன் நான், சண்டைக்கு வந்தா சவால் விட்டா, தடியத்தான் புடிச்சித்தான், கை விரலில சுத்துற சுத்துல, அண்ணாச்சி உன்ன நான், புண்ணாக்கு தின்ன வைப்பேன்!".

Then, when the climax hits and Sivanaindhan clutches his stomach and I’m supposed to believe it’s from hunger. But instead, it looks like he’s just bloated and wants to take a shit at the nearest plantation. This should be a moment that resonates, that tears at you, but it doesn’t. It feels completely disjointed from the screenplay. It feels completely disconnected from the heart of the film. I can’t connect even if I try, because no emotional investment was built up. If hunger is supposed to be this pivotal, why hasn’t it been earned?

Before I close this chapter, here’s a breakdown of the shot economy in Vaazhai to illustrate with clarity just how much time and space are dedicated to the narrative elements of the film:

- From the opening to the director’s billing credit: 12:57 seconds

- All the union drama: 9:58 seconds

- Sivanaindhan and his sister's relationship: 6:39 seconds

- All the plantation scenes across three songs: 7:56 seconds

- Teacher's portion, including school-related scenes: 38:53 seconds

- Sivanaindhan gets off the truck for the dance: 2:18 seconds

- The interval block with the broker scuffle: 4:48 seconds

Total run-time (from opening director's disclaimer to the end credit crawl): 2 hours, 12 minutes

Total screen-time for the above moments: 1 hour, 23 minutes

That leaves 49 minutes for establishing Sivanaindhan’s hunger.

Yet, from the moment the teacher exits the frame to when Sivanaindhan finds food, we get just 7:26 minutes. So where’s the other 41 minutes? What happened to that time? Why am I only handed this pivotal moment in passing, with no subtext to anchor it in the broader narrative or the development of Sivanaindhan's character? Why was this opportunity missed, especially when the emotional weight of hunger is positioned as such a crucial moment? The question here isn’t merely logistical—it’s deeply emotional.

A Brief Contextual Interjection

I tend to ground my analysis in what’s presented on the screen—what's in the frame, the subtle nuances of performance, and the visual storytelling. But with Vaazhai, the necessity to look beyond the film itself becomes unavoidable. The real-life tragedy that’s intricately woven into its narrative demands a deeper consideration, one that transcends the film’s confines.

To gain a deeper understanding and further contextualize the film, I reviewed a number of interviews and press materials surrounding both the narrative and its real-world tragedy. Additionally, I read மறக்கவே நினைக்கிறேன் and unfortunately, I was unable to access தாமிரபரணியில் கொல்லப்படாதவர்கள், as the book is unavailable on this side of the ocean.

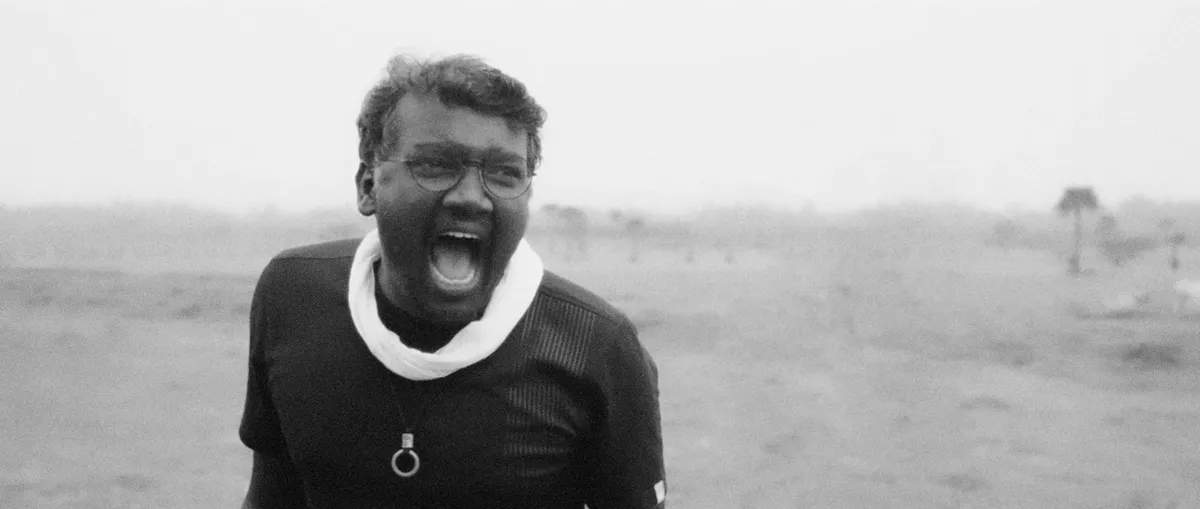

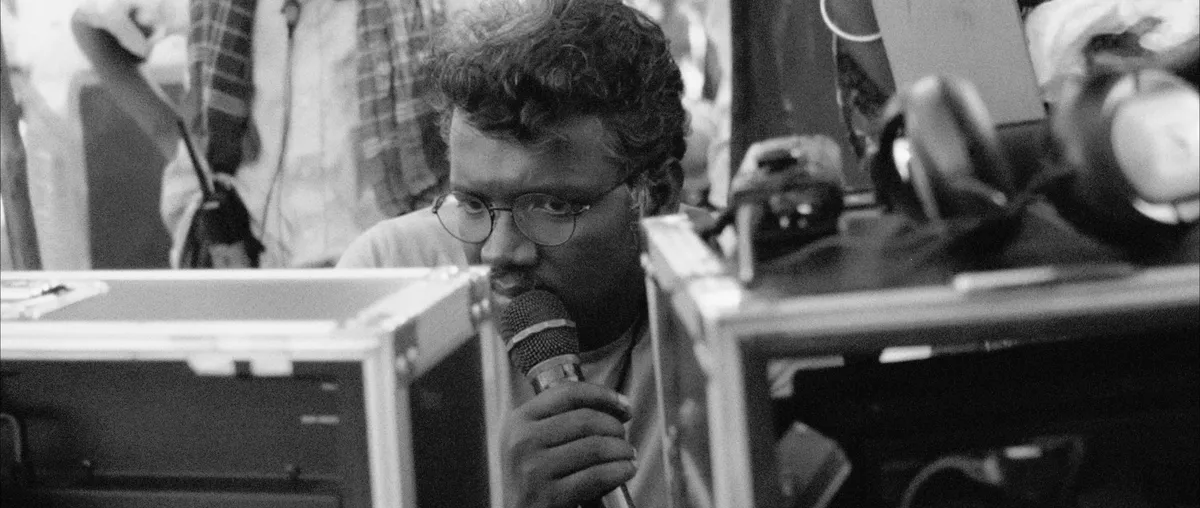

What I gathered after extensively going through the extra material left me unsettled. Mari Selvaraj, the writer/director, seems to exist in a space somewhere between a perplexed artist and a charlatan. There is certainly a tension, an ambiguity in his presence, as though he is caught between the desire to project authenticity and the uncertainty of his own journey.

My confusion is rooted in the weight of Mari Selvaraj’s claim—how deeply personal he positions Sivanaindhan, almost as if it is a mirror to his own life, a biographical testament to his experiences. The inspiration for the story looms as a towering monument of traumatic memory he has long struggled to confront. He speaks with such conviction about the film’s intimacy and intensity, yet when I watch it, that connection, that raw truth, feels elusive. There’s a quiet slothfulness in the execution. The gap between what he promises and what is delivered is vast. It feels as though something has been left out, deliberately concealed, leaving a raw, unspoken void.

In the chapters to follow, my intention is to move beyond the director’s public persona and attempt to understand him as a human being. What lies beneath the surface of his films? What is the story he is unwilling to tell, or perhaps, too fearful to confront? What is the tension between the vulnerability he seeks to express and the guardedness that keeps it at bay? By exploring these questions, I hope to uncover the complexities that resides in the spaces between the frames.

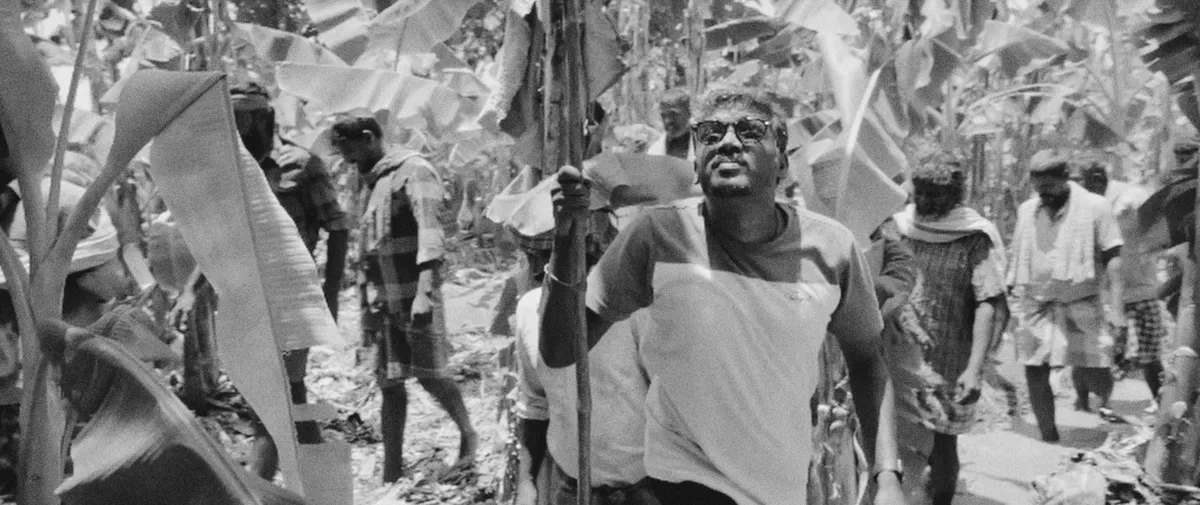

Oppression Over Character: A Hollow Narrative

Mari Selvaraj’s approach to storytelling is built on a curious claim: his stories aren’t rooted in factual tragedies. Instead, he asserts them during the filming and scriptwriting process, he "recalls" events from his own life that just so happen to closely mirror real-world circumstances—and injects them into the narrative. To put it simply, the factual tragedies are reduced to mere parentheses, while his lived experience functions as the bookends, framing everything in a personal context. It’s a technique that smacks more of self-indulgence than genuine exploration, reducing the potential for universal resonance in favor of a solipsistic, one-note reflection.

Think of him as a crate junkie, scavenging for samples from other people's work to repackage and put his own spin on, hoping to create something "new." But the truth is, all he's doing is remixing, layering his personal narrative on top of others, without fully committing to the depth or complexities those original sources demand. It's not originality. It's an attempt to mask the lack of it with borrowed pieces.

What’s striking here is that his focus isn’t even on the characters. He’s obsessed with oppression, with turning it into a villain so he can position himself (or his protagonists) as the hero—always saving the day, like it’s some kind of self-congratulatory performance. This approach, in turn, cultivates a dangerous rhetoric. Because in his worldview, he will always be a victim—forever externalizing any hurt, never once turning inward to confront the complexities within.

This ideological stance is glaringly evident in the scene where the daughter attempts to persuade the mother to stop Sivanaindhan from continuing his work. The mother embodies a set of sharp contradictions—on one hand, she clings to the pride of her late husband’s struggle for workers' rights, yet on the other, she is immobilized by the fear that her children will suffer the same fate. In the name of preparing her son to fend in a harsh world, she sacrifices his future by denying him education, opportunity, and the very means to transcend his circumstances. Every choice she makes only drags him deeper into the very system she’s trying to protect him from. The conflict here is undeniable. But what does Mari Selvaraj ultimately choose to do with it? How does he navigate this tension?

He seems to actively avoid digging into the more complex emotional dimensions of the conflict. Instead of using the mother's contradictions and her internal struggle to truly explore the nuances of her motivations and impact, he resorts to focusing on the broader systemic forces. It’s a shitty, shallow, and self-serving approach that robs the characters of any real depth and reduces their stories to nothing more than a convenient lens for his ideological rant.

The absence of a counterpoint—especially from the daughter—diminishes the emotional stakes. It would have been far more powerful if the daughter had pushed back, questioned the validity of her mother’s logic, and probed what real benefits this philosophy has provided them? More pointedly, what has it given her personally? After all, it’s the daughter who ultimately bears the brunt of the tragedy. Such a confrontation could have deepened our understanding of their relationship, allowing for rich emotional development and setting the stage for the climax. An opportunity for depth lost in pursuit of an ideal.

Trauma without Drama: Omitting the Opposition

In Chapter 13 of மறக்கவே நினைக்கிறேன், Mari Selvaraj opens with a series of questions that, on the surface, promise to delve deeper into themes of identity, oppression, and societal structures. But just like Vaazhai, as the chapter unravels, it becomes painfully obvious that these questions aren’t there to provoke real introspection; they function as carefully constructed devices—crafted to nudge the audience toward a predetermined conclusion.

ஆணாகப் பிறப்பவர்கள் என்னவெல்லாம் ஆக முடியும்? அப்பாவாக, மகனாக, அண்ணனாக, தம்பியாக, நண்பனாக, எதிரியாக, துரோகியாக,பைத்தியக்காரனாக... முடிந்தால் தலைவனாக! அதே போல் பெண்ணாகப் பிறக்கிறவர்கள்? மகளாக, அம்மாவாக, அக்காவாக, தங்கையாக, அண்ணியாக, தோழியாக, காதலியாக, மனைவியாக, முடிந்தால் தெய்வமாக!

This perspective on societal roles, valid as it may be, also exposes why there’s a glaring absence of drama in Vaazhai. I’m fully aware that, compared to the majority of Indian men, this hierarchy isn’t exactly groundbreaking. But in my opinion, it’s this very rigid, paternalistic structure that stifles creativity, suffocating the emotional depth of Vaazhai and ultimately crushing any ability to fully express something complex. When characters are confined to predefined, sacred roles, there's no space for the kind of subversion that makes a story resonate. Besides, who else but A.P. Nagarajan had the balls of adamantium to challenge தெய்வம்?

Mari Selvaraj claims to tear down hierarchical conventions at every turn, but in reality, what he's really doing is trapping his characters—particularly the women—into preordained roles that leave little room for complexity or growth. The true power, the real breakthrough, comes when we allow contradictions to sit, unfiltered, and let people be messy—when we let them breathe in all their contradictions, flaws, and vulnerabilities. That’s where real transformation begins.

The lack of a counterpoint in the mother-daughter exchange might simply stem from Mari Selvaraj’s inability to craft meaningful dialogue, let alone grasp the psychological complexity of women, or perhaps a deeper failure to confront his own understanding of responsibility. Or maybe—just maybe—he didn’t have any "recalls" to draw from, because, conveniently, his real-life sister முருகம்மாள் இப்போது ஸ்டேட் பாங்க் ஆஃப் இந்தியாவில் பணிபுரிகிறாள்.

In the same vein, the conflict between the mother and son at the beginning, where she reluctantly tells Muthuraj, the broker, that she will send Sivanaindhan to work—or the interval block—could have been a searing exploration of sacrifice, generational trauma, and the painful limits of parental love. Instead, Mari Selvaraj chooses to completely sidestep this emotional complexity, opting for a superficial approach that never fully engages with the depth of the situation.

In relationships, whether between a mother and daughter or any family members, the real depth is found in the push and pull—the questioning, the confrontation, the vulnerability. Drama, at its best, recognizes that in any argument, everyone is, in some way, right. Each perspective carries weight, and it’s that tension between opposing views that fuels the complexity of conflict. If one character’s beliefs are upheld while the other’s dissolve, the narrative loses its energy and falls flat.

Without that complexity, all you’re left with is cosmetic dialogue that lack the emotional and thematic stakes that give a story its weight. From where I stand, it seems like Mari Selvaraj selectively chose what to reveal, intentionally omitting the hard truths lurking beneath the surface. To me, that’s a cop-out, a way to avoid confronting the real messiness of human experience. A disagreement is not the same as disrespect.

Trauma without Truth

Mari Selvaraj has openly stated in interviews that his films serve as a way for him to process trauma—a vessel through which he can contain the chaos within and present it to the world. This much is evident. However, what’s troubling is how he adapts the complexity of that trauma on screen. The result is not a connection. I don’t feel invited to witness or take part in something deeply personal, instead, it feels like it’s being shoved in my face.

A traumatic event does not reveal itself in a single moment; it unfolds gradually, like a shadow that stretches and morphs, ever-present yet unseen. It seeps in slowly, bit by bit, until it has woven itself into the very core of your being. It erodes your sense of stability, subtly undermining your foundation, until, one day, you find that the ground beneath you has shifted, and you no longer stand where you once did. The harm may not be instant, but it leaves a mark that’s hard to erase.

To confront, let alone resolve, it requires a prolonged and painful introspection that forces you to question everything you once took for granted, to trace those beliefs back to their roots—and even further, to examine the very pathology beneath them. More often than not, you find yourself dismantling every piece of the wreckage, carefully examining each fragment, before trying to rebuild yourself, seeking freedom from that burden. And even then, there’s no assurance it will ever truly depart. It becomes an ongoing negotiation, a daily effort to keep the past at bay, to hold it at arm’s length while trying to engage fully with the present.

Vaazhai could have been—an unflinching dive into the rawest, deepest scars of vulnerability—but it remains forever just out of reach. It could have been a film that moved with an unforgiving emotional force, one that tore through every frame with a brutal, unrefined truth. Instead, what I'm left with is a sterilized version of trauma—neatly packaged, controlled, and never truly daring to expose the unvarnished pain it claims to address.

As outlined earlier, in his attempt to anchor his narrative in “recalls,” Mari Selvaraj binds his story to real-world tragedies. Yet, in doing so, he does not merely misrepresent loss—he divorces himself from the very essence of his own experience. It's a lose-lose situation. The layers of self-deception he drapes over it suffocate the real truth, muting the very pain that could have given the film its soul.

Rather than immersing himself in the depth of trauma with the aid of the cinematic vessel, Selvaraj hovers at the periphery, too hesitant to submerge fully into the murky waters of real pain. This unwillingness to confront the messy, uncomfortable truths leaves Vaazhai stagnant, disconnected from the emotional complexity it pretends to present. Vaazhai isn’t the narrative of trauma it aspires to be. It is a narrative of avoidance—a tragedy that wears the façade of depth without ever daring to confront its unvarnished core.

What You Reveal, You Heal

Some writers, when grappling with real-life tragedies, possess the uncanny ability to make the tragedy not just a part of the narrative but the narrative itself. They dive deep into human suffering, and through the skillful weave of their craft, they allow the audience to touch it, to feel it on a visceral level. This isn't just storytelling—it's an exploration of the human condition.

Mari Selvaraj, the writer, on the other hand, frequently inserts himself so aggressively into the frame that the tragedy takes a backseat to his own presence. His desire to be seen, to imprint his own story onto the screen, shifts the focus away from the collective pain and into his own personal narrative. In Vaazhai, what’s immediately apparent is that he doesn’t just craft a story of trauma—he stages his own exorcism. But in doing so, he stumbles.

There’s an undeniable tension between his need to heal and his refusal to confront the core of that pain. This struggle has woven itself into the very fabric of his identity as a writer. He holds himself back, caught in a game of mimicry, projecting his own struggles onto his actors. His approach feels as though he vicariously lives through them, mimicking rather than communicating. Beneath it all, there’s a quiet, yet desperate, plea for recognition—as though by inserting himself into the tragedy of others, by re-enacting pain, he believes he can somehow find penance for his own actions. Yet, he fails to recognize that true transformation never comes from control—it comes from vulnerability.

His stories are a projection of this paradox. There is no room for forgiveness. There is no space for reconciliation. His anger shifts from personal to political, but the inward journey—the journey of self-reflection—is missing. The catharsis he seeks will never arrive until he is ready to face the full complexity. Only then, when he embraces the messiness of his own soul, can he find any semblance of peace. I feel like he’s perpetually standing on the edge, about to shout, "It’s not about what I want, it’s about what’s fair!"

Apathetic Rebel

Every day, people are dying. And we all feel it. Some more than others. The closer we are, the sharper the sting. But, to sit here and assert that my tragedy holds more weight, that my grief demands a greater share of attention—this is a kind of arrogance that is almost unbearable. To claim that your tragedy should overshadow others, that your pain is the one we must care for, to demand that the universe pause in reverence—on whose authority? What makes your anguish more significant than someone else's? Who said you alone have the high ground of virtue, of moral righteousness? This continual struggle to elevate oneself by stepping on the grief of others—honestly, it’s fucking exhausting.

Some people claim to care about every injustice, but what does that truly mean? To care isn’t just to express discomfort or offer a fleeting opinion. It’s about commitment. It’s about giving focused attention, devoting yourself to something with purpose, and ensuring that what you care about isn’t lost in the noise.

The truth is, the serious problems in the world require hard, sustained work. They can’t be solved by just acknowledging them from a distance. So how can we claim to care about everything when we live in a world that demands focus, discipline, and depth, yet we still try to spread ourselves thin—committing to every cause, every injustice at once? To truly care is to narrow your focus, to understand that real change comes from that discipline, not from trying to be everything to everyone.

I wish someone would take Mari Selvaraj’s hands and say, "I hear you, truly. I understand the burden you're carrying." And then gently remind him that every choice, every path we walk, comes with a cost to you and an expense to someone else. There is no remedy. In the end, it's not the bold proclamations that matter most—it’s the quiet, thoughtful acts of compassion that have the power to heal, to connect, and to truly make a difference. Those are the moments that count.

When Insecurity Defines the Frame

Unlike Mari Selvaraj the writer, as a director, he occupies a position of greater maturity—one that should allow him to confront the darker, more nuanced aspects of his own experience. He certainly claims this, but there’s a hesitation that can't be ignored—an aversion to fully committing. It’s not about artistic clarity or economy. It's something deeper. Something personal that he can't quite bring himself to expose. To reveal certain aspects of his narrative would mean exposing a vulnerability that transcends mere personal disclosure—something that destabilizes the very structure he’s crafted.

This isn’t about rebellion against societal structures or throwing punches at the so-called "gatekeepers", nor is it about embodying some form of anti-establishment bravado. No, this is a quiet, internal fear that whispers: If I expose this side of myself, it’ll shatter the very framework I’ve built and upend my paradigm. So, he holds back, not out of artistic restraint, but out of self-preservation.

By sidestepping this reckoning, he avoids the unapologetic, unforgiving collision between the personal and the political—a confrontation that could have imbued his film with an unrelenting dangerous edge. An edge that would have thrusted him into the very stratosphere of not merely a radical director, but a true artist of consequence as he so desperately wants to be. For all Mari Selvaraj’s confident claims, what he delivers on screen reeks of insecurity. The contrast is glaring—he flirts with depth but never fully plunges into it.

At this point when he wins another predetermined award, he might as well say எல்லாரும் கேட்டுக்கோங்க நானும் மரபுகளுக்கு எதிரான திரைப்படம் எடுக்கும் ஒரு பெரிய இயக்குனர்! ஒரு பெரிய இயக்குனர்! ஒரு பெரிய இயக்குனர்!

After all, It's Cinema

At the end of the day, Vaazhai is cinema—an audiovisual experience, not just another memory etched in the pages of a confessional diary for quiet reflection. This is where cinema departs from literature. For me, the screen is a battlefield, where light and shadow clash, where sound and movement are weapons used to dismantle you and put you back together again. There’s no room for slack or meandering. Cinema is a discipline. A precise art form that demands precision, control, and, above all, purpose.

You can’t just throw your pain onto the screen and expect the audience to feel it because you say so. Trauma, like violence, can’t just be paraded in front of the audience for shock value or dramatic effect. It has to be felt. I have to feel the weight, the horror, the devastation of it. If I walk away unchanged, untouched, then the fault lies in the craftsmanship of the narrative.

Mari Selvaraj hands me his pain, his experience, and says, “Here’s the weight. Now, you carry it too.” And that’s it. No depth, no exploration—just the raw sensation of the burden without any of the insight that might make that burden meaningful. And that, to me, feels cheap.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with presenting the trauma as is, but if you’re going to do that, you need to be a master communicator, using every cinematic tool at your disposal with laser precision. It better be airtight—like a veteran comedian’s stand-up set, where every beat, every pause, every word is meticulously crafted. Every phoneme, every moment on screen should reflect, should resonate. It has to land. It has to cut through. Otherwise, it’s just noise. If the execution lacks this clarity, the film falls short. Bottom line—you better be damn fucking good at what you do, and Mari Selvaraj just isn’t.

Furthermore, Vaazhai is buried under a series of technical missteps: inconsistent and uninspiring lighting, flat framing, and focal inconsistencies that distract rather than engage, disjointed sound design, vinyl scratch editing, sound mixing that lacks nuance, and the choice of music, at times, feels disconnected from the narrative’s pulse—anachronistic in ways that disrupt rather than elevate the atmosphere. அவன் நிமிர்ந்து பார்த்தா வானம்... குனிஞ்சி பார்த்தா பூமி... no shit Sherlock! And, of course, the inevitable lipsync issues persist. At this point in recorded cinematic history, it’s nothing short of a தமிழன்டா! tradition—a stark reminder that, despite having access to the most advanced tools, we've somehow managed to regress. These technical missteps create a pervasive pattern throughout the film, ultimately dulling its emotional impact.

The Power of Cinema

Filmmaking is a medium that demands more than just technical prowess. It’s about communication at the end of the day. It's about the ability to make people feel something. Media as a whole isn’t just a tool—it’s a bridge. A bridge between minds, between lives. Mari Selvaraj needs to recognize that it is through images—that he has the opportunity to witness the tragedies he claims as his own. Images hold immense power, more than we often realize. They carry weight. They bear consequence.

I have no doubt—absolutely none—about his knowledge of literature. But, to take words and synthesize them into a visceral experience through steel, aluminum, plastic, glass, lumen, candela, amperes, ohms, texture, clay, pattern, pigment, timbre, chords, sheet, data—now that requires a rare kind of artistry.

A shot, a scene, a sequence, a cut, they are not mere mechanics—they are the embodiment of a thought. To take the real, the seen, and transform it into the unreal, the felt. It’s a pursuit that takes a lifetime, a commitment that goes far beyond the written word, constantly pushing the boundaries of what can be seen, heard, and felt. It demands a deep understanding of the human experience itself.

But to stand there with clenched fists, railing against everything, without a true grasp of what you're fighting for—that’s not a path to a deeper understanding of the human condition. It’s a façade. The same audience that once cheered you, drawn in by your defiance, your boldness, will eventually start to pull away. When the rebellion has no weight behind it, when the challenge of conventions is nothing more than a hollow gesture, they’ll feel it. It’s not about breaking rules just to break them. It’s about knowing why you break them, and understanding the deeper resonance that comes from doing so in a way that serves the story—not just the spectacle.

Between the Moments

People who can lose themselves in watching the same movie in a thousand different variations—I envy them, in some twisted way. As Hannibal Lecter would say, "I myself, cannot." I can't settle for the comfort of familiarity, repetition without purpose. And I can't afford to waste time on that.

Perhaps it’s a sign of my own limited exposure to modern cinema, but there’s something about the way films are structured these days that doesn’t quite sit right with me. The growing tendency to rely on moments—those brief flashes of emotional intensity or high-stakes drama, as if they alone are enough to carry a film. A moment, or even a collection of moments, is simply not enough. Not for me, at least.

It’s easy to manufacture a moment and it will undoubtedly land with an audience. But what’s far harder—and what I believe truly tests a filmmaker’s skill—is the work that goes into building the pith between those moments. The stillness of life, the subtle interactions that weave the fabric of the entire story, the characters, and everything in between. It's the space between heaven and earth—the unspoken, the quiet, the mundane—that binds everything together, making the moments that much more meaningful. They’re the foundation on which everything rests.

Cinema is an art form that, when wielded with true mastery, can transcend its medium, its limitations, even its audience. Therefore, the rules matter. The form matters. The science behind it matters. You can’t just skip the fundamentals of storytelling in the name of "tearing down conventions" and expect me to keep up.

I'm all for tearing down the conventions of storytelling. But let’s not forget that to truly dismantle the conventions, one must first be intimately fluent in those very conventions. When you cannot even establish your main character performing the simplest of tasks, like sleeping, without resorting to gimmicks—it's a clear sign that your foundation is still weak.

Look no further than the final slide of a newspaper clipping. The article—a fleeting glance on a page—carries more weight, more potency, than the film ever could. The brevity, the precision, it echoes. It’s an odd thing to consider: how something so brief, so easily dismissed, can hold more resonance than an entire cinematic journey. The film never seems to capture the concentrated force of a few well-chosen words, neatly folded into the space between columns. It cuts through in ways that the film, for all its grandiosity, cannot match.

Mari Selvaraj claims that Vaazhai is more than the sum of its parts, but I couldn’t disagree more. Vaazhai is exactly that—it's even less than that. Each element, each choice, should contribute to something greater, something cohesive. Instead, they collapse under their own weight.

As I sit with these thoughts...

If I could sit down with Mari Selvaraj, the conversation would be nothing but encouragement, but focused on his personal side. The artist within. The inner boy who still carries his hurts. I would urge him to fully engage with the darkness of his own experience, both as a character and as a filmmaker. In his work, Mari Selvaraj employs dramatic irony in a way that unintentionally limits the audience's ability to connect on a deeper, more transformative level. As a result, the trauma remains unresolved, suspended in stasis—never allowed to break free and genuinely confront the painful complexities of suffering and personal growth.

Aggression, at its core, is not just a force to be feared—it’s a compelling power. I sincerely believe that there is fucking beauty in aggression. In Mari Selvaraj, there’s a storyteller, a creator, lurking just beneath the surface of this perplexed, translucent barrier—a delicate hymen between what he desires to express and the part of himself he’s unwilling to fully reveal. An artist, when properly nourished in the art of communication, has the ability to cut through the noise. After all, he has four features under his belt, and that’s no small feat, regardless of how fucked up or low the entry to the industry may be. It’s a mark of persistence, of ambition. That's commendable.

I don't think he's a charlatan. I believe, much like many men, his pain is not unique, but rather amplified—taken to a degree that perhaps only he feels. His anger, however, isn’t misplaced; it’s displaced, a reflection of the inner turmoil he’s not yet able to confront. The hurt is real, but the way it manifests is a projection of something deeper, something he hasn’t yet learned to name. I just hope he gets to name it one day. Until then, everything he creates will remain nothing more than a faint, hollow echo of the raw power it could have been. சிலருக்குச் சில நேரம், துணிச்சல்கள் பிறக்காது, துனிச்சல்கள் பிறக்காமல், கதவுகள் திறக்காது!

Thanks for reading,

V.